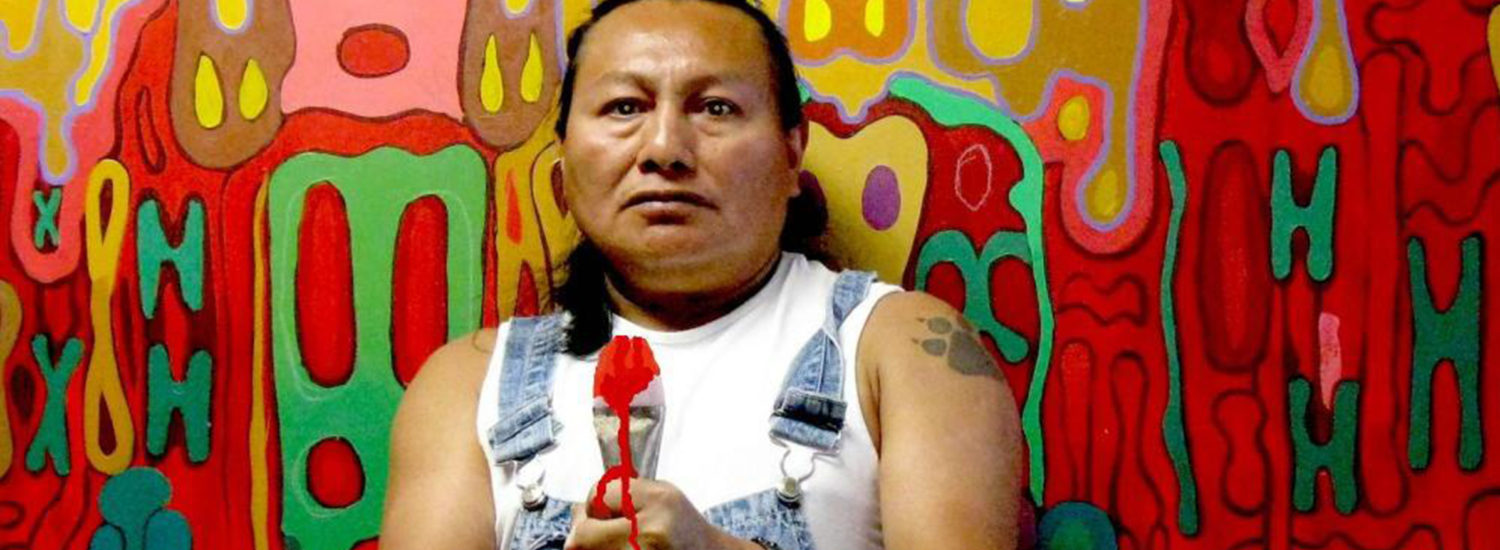

Oswaldo De León Kantule

Oswaldo De León Kantule was born on the island of Ustupu in Kuna Yala, the archipelago of islands along the Caribbean coast of Panama. He is a painter and scholar of Kuna culture.

Oswaldo De León Kantule, called “Achu,” graduated from the Faculty of Fine Arts at the University of Panama. He now lives in London, Ontario, with his wife Angela Laird, a teacher and translator, and their children Sebastian and Nayli.

In July 2010 his paintings — full of ancestral symbolism — were exhibited at the Museum of Contemporary Art in Panama City in a solo show called Entre signos, símbolos y señales. He was the first Kuna artist to be so honoured.

Oswaldo De León Kantule is the great grandson of Chief Nele Kantule [Iguaibilikinya Nele Wardada Kantule] one of the two leaders of the 1925 Kuna Revolution. For many decades Panamanian government officials and missionaries had tried to “civilize” the indigenous Kuna people by encouraging — or forcing — them to give up their beliefs and customs. In 1925 the Kuna fought back. During the brief uprising, the Panamanian governor, police, teachers, and missionaries fled from the Kuna islands, known then as the San Blas islands.

Eventually in 1938 a self-governing province called Kuna Yala was established as a part of Panama. It included all the Kuna islands and a strip of adjacent territory along the coast. Today the Kuna are recognized as one of the world’s most politically sophisticated indigenous groups.

The Kuna

The Kuna people live on an archipelago of over 300 small islands just off the Caribbean coast of Panama. The islands lie very low, just a bit above sea level. And the sea level is slowly rising.

Some of the islands are a kilometer away from the coast, reached by canoe, and others are so close you can wade to them. Plans are being made on several of the islands to move the inhabitants to higher ground on the mainland to avoid the rising water.

Another problem faced by the Kuna is the amount of junk and debris, including discarded plastic water bottles, washed ashore and littering the islands. The junk is coming from cruise ships and from the Caribbean currents that deposit rivers of plastic debris on the beaches of Kuna Yala.

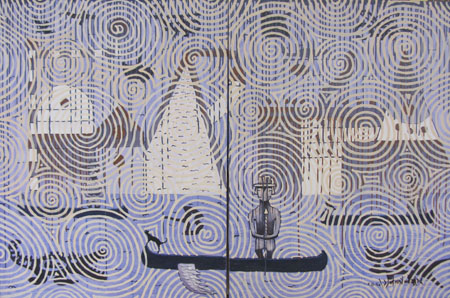

Many of Oswaldo De León Kantule’s recent paintings reflect these environmental issues: some show figures and landscapes rippling like melted plastic (Phantoms of the city, #6), others show Kuna spirits swamped by rising water (Kuna Yala submerged, #1 and Waiting for our island home to sink, #10).

The Kuna say that the cosmos consists of eight levels. On some of the invisible levels there are structures called galus that are inhabited by the spirits of everything animate and inanimate.

Elaborate verbal narratives and chants about creation and Kuna history are the primary art of Kuna men, who rarely make graphic art. Both men and women are involved with music and dance; the men play pan flutes and the women play maracas. Men also carve figures called nuchus, usually in human form, that serve as spirit helpers.

Kuna women are admired around the world for the elaborate textile panels called molas that they make and wear on their blouses. The mola panels consist of layers of cloth — like the layers of the cosmos — which are cut through with scissors, appliquéd and embroidered to create brilliant multicoloured pictures.

The mola panels depict Kuna legends, or animals and plants, or graphic images from package labels, book illustrations, movies, posters, advertisements, television programmes … the list of sources is endless. There was an exhibition of molas called Drawing with Scissors at the Textile Museum of Canada in Toronto. The exhibition included related paintings by Oswaldo De León Kantule.

There are not many painters among the Kuna. The art of Oswaldo De León Kantule is thus a rarity. But all his paintings embody traditional Kuna beliefs and ancestral symbolism.

The Kuna tell an elaborate story about how the world was created, what it was like before the Kuna arrived, and how the Kuna came to exist. This enormous narrative, called The Way of the Father, is peopled with beasts and spirits, whirlpools and tornadoes, and culture heroes — human and otherwise.

All the Kuna arts, including storytelling, emphasize metaphor and duality, in which one thing suggests another. All the arts use repetition and symmetry, reflecting the Kuna concept of akala-emala, “the same only different.”

Many of Oswaldo De León Kantule’s paintings are paired, or symmetrical, with one side reflecting the other. Swirling water is everywhere, as it is in Kuna Yala. There are shamans and nuchus (the carved figures that serve as guides through the eight levels of the cosmos), transported on canoes. The galus, or spirit structures, are based on shamanic descriptions and coded drawings. Mystical jaguars and sea creatures like swordfish and manta rays abound.

Hammocks often appear in the paintings, symbolizing the heart of the Kuna people, who sleep in hammocks. Chiefs chant from hammocks during meetings. When someone is ill, they lie in a hammock while a healer uses medicines against the forces causing the illness. At the end of life, the dead are buried in a hammock, suspended in a hollow grave below ground.

Curated by:

Max Allen