Ontario Place is a mirror to show you yourself. Your heritage. Your land. Your work. Your creativity. And your tomorrow.

—Ontario Place promotional brochure, 1969

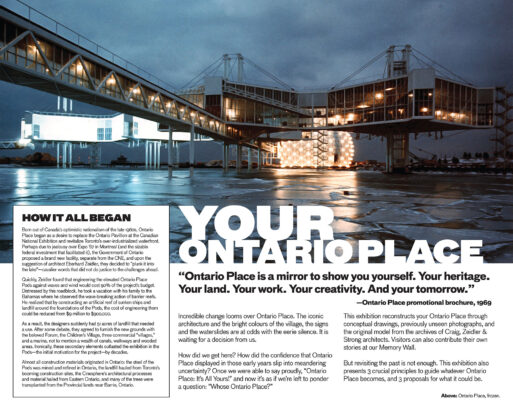

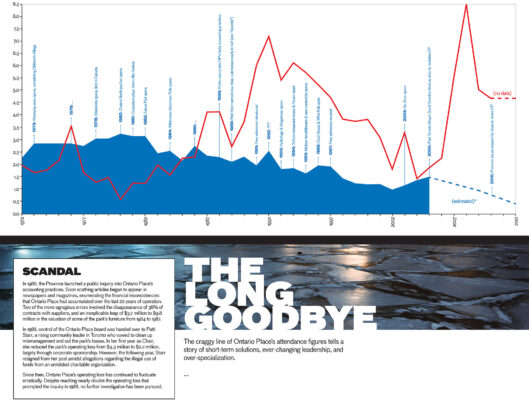

Incredible change looms over Ontario Place. The iconic architecture and the bright colours of the village, the signs and the waterslides are at odds with the eerie silence. It is waiting for a decision from us.

How did we get here? How did the confidence that Ontario Place displayed in those early years slip into meandering uncertainty? Once we were able to say proudly, “Ontario Place: It’s All Yours!” and now it’s as if we’re left to ponder a question: “Whose Ontario Place?”

This exhibition reconstructs your Ontario Place through conceptual drawings, rare photographs, and the original model from the archives of Craig, Zeidler & Strong architects.

HOW IT ALL BEGAN

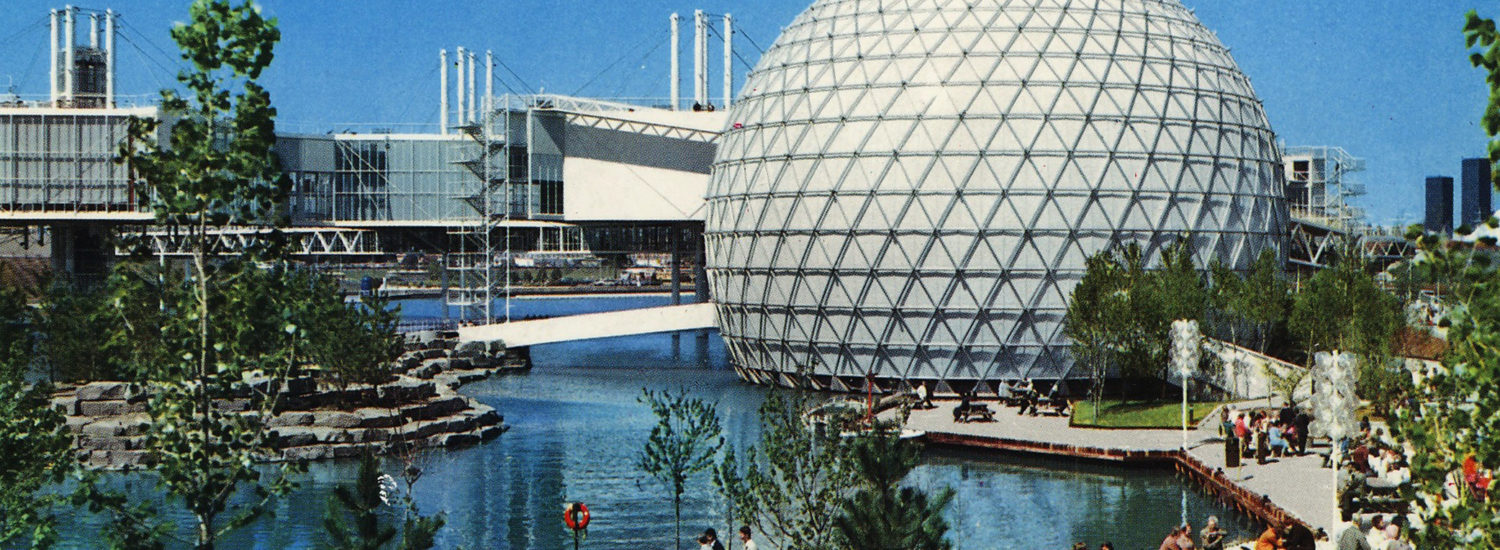

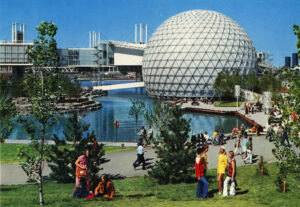

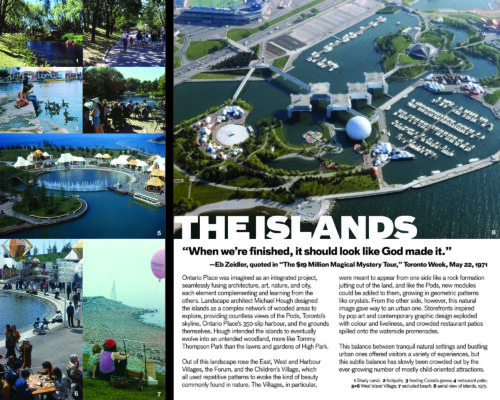

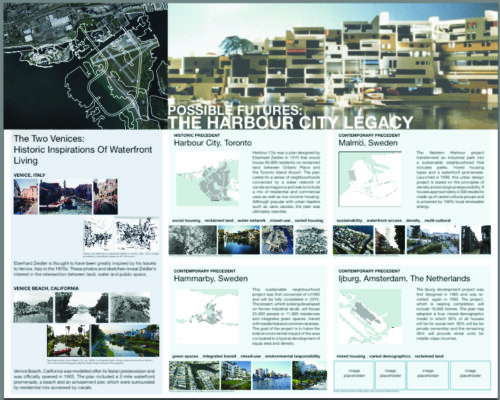

Born out of Canada’s optimistic nationalism of the late 1960s, Ontario Place began as a desire to replace the Ontario Pavilion at the Canadian National Exhibition and revitalize Toronto’s over-industrialized waterfront. Dazzled by Expo ’67 in Montreal, the Government of Ontario proposed a brand new facility, separate from the CNE. And upon the suggestion of architect Eberhard Zeidler, they decided to “plunk it into the lake”— cavalier words that did not do justice to the challenges ahead.

Quickly, Zeidler found that engineering the elevated Ontario Place Pods against waves and wind would cost 90% of the project’s budget. Distressed by this roadblock, he took a vacation with his family to the Bahamas where he observed the wave-breaking action of barrier reefs. He realized that by constructing an artificial reef of sunken ships and landfill around the foundations of the Pods, the cost of engineering them could be reduced from $9 million to $900,000.

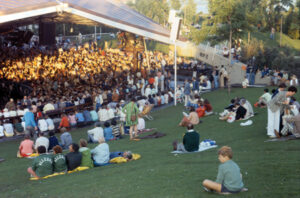

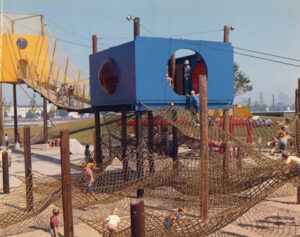

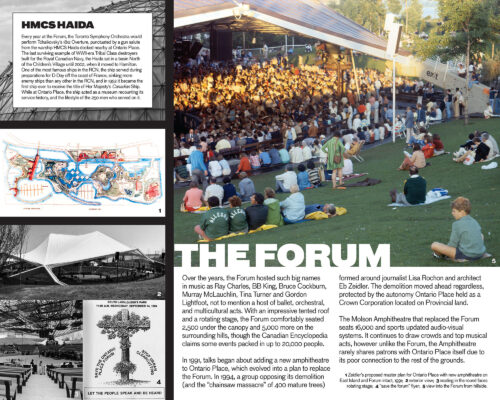

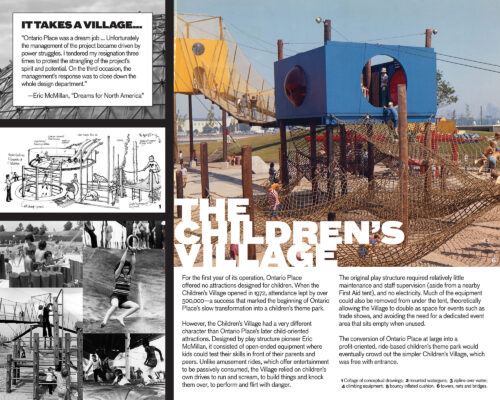

As a result, Zeidler and his collaborators suddenly had 51 acres of landfill that needed a use. After some debate, they agreed to furnish the new grounds with the beloved Forum, the Children’s Village, three commercial “villages,” and a marina, not to mention a wealth of canals, walkways and wooded areas. Ironically, these secondary elements outlasted the exhibition in the Pods — the initial motivation for the project — by decades.

Almost all construction materials for the project originated in Ontario: the steel of the Pods was mined and refined in Ontario, the landfill hauled from Toronto’s booming construction sites, the Cinesphere’s architectural processes and materials hailed from Eastern Ontario, and many of the trees were transplanted from provincial lands near Barrie.

Curated by:

Nathan Storring